This Associated Press feature profiles Bayard Rustin as the chief organizer of the March on Washington, tasked with orchestrating a massive, military-scale logistical operation just weeks before the event. It also confronts the personal attacks used to discredit him, highlighting Rustin’s transparency, commitment to nonviolence, and central behind-the-scenes role alongside A. Philip Randolph.

Historical Context

By August 1963, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was a source of intense national scrutiny. Segregationist politicians were actively using Rustin’s sexuality and former political ties to "red-bait" the movement, hoping to undermine its credibility. The movement's leadership had to navigate these sensitivities carefully.

This article reflects a specific moment where Rustin’s organizing genius became a matter of public record. By framing the march as a campaign of "precision," Rustin was responding to fears of disorder, assuring the public that the event would be disciplined. His work involved a massive coordination of various groups, including the SCLC and CORE.

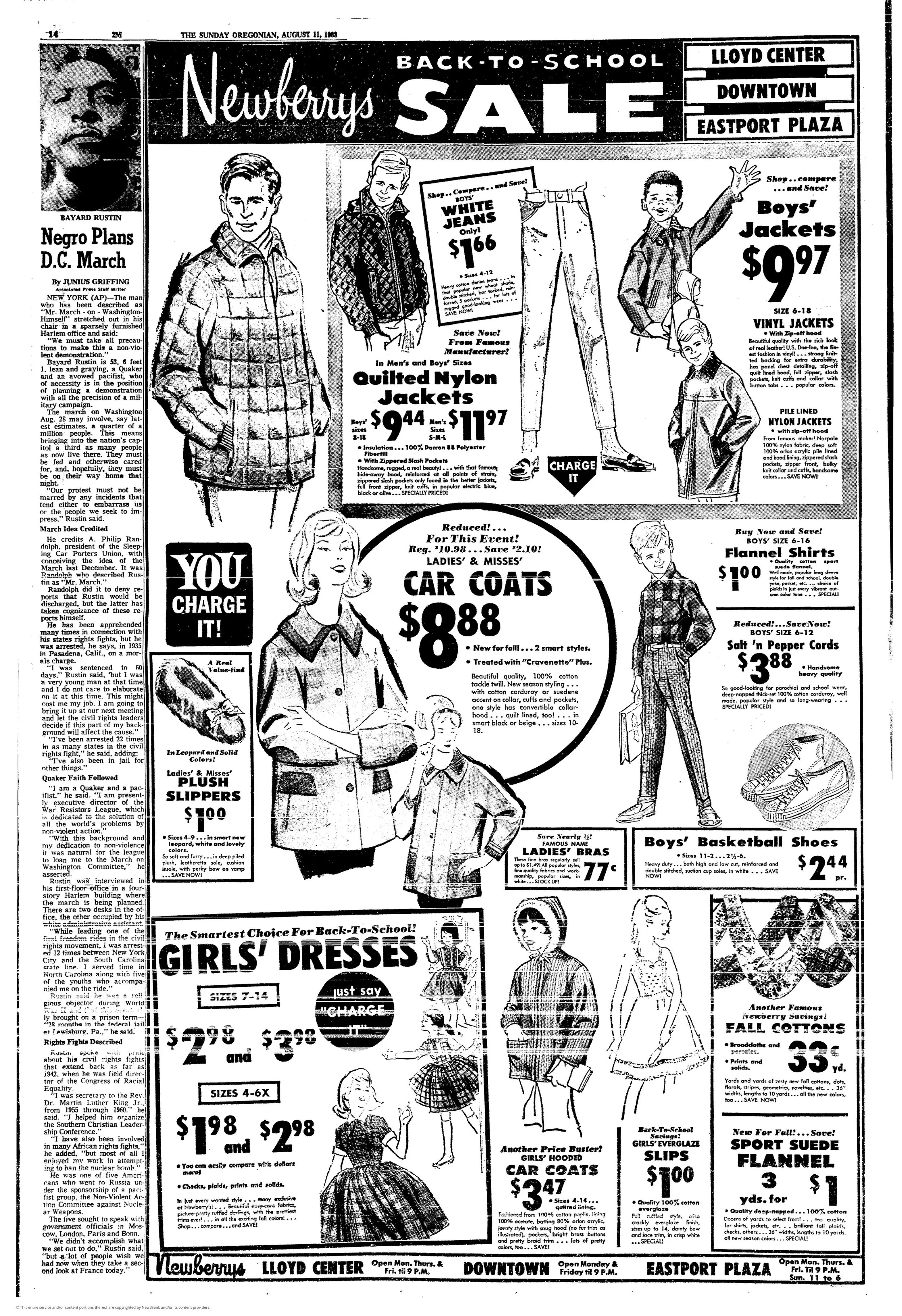

The visual context of the original page is striking Rustin’s profile is positioned next to "Back-to-School" advertisements for Newberrys department store. This juxtaposition highlights the era's social landscape—a mid-century consumer culture focused on "quilted nylon jackets" and "girls' dresses" while Rustin prepared to lead a landmark demonstration for civil rights. The article shows Rustin using his Quaker values to bridge his "private life" and public mission, insisting that nonviolence could meet "all the world's problems"

Description

This Associated Press feature, appearing in The Sunday Oregonian just seventeen days before the March on Washington, captures Bayard Rustin in his Harlem office. The report details Rustin's immense responsibility: coordinating the arrival, safety, and movement of what was then estimated to be a million people—a crowd equivalent to one-third of the population then living in D.C. Rustin describes the logistical feat as requiring the "precision of a military campaign".

The article explicitly addresses the "prejudice" and "personal attacks" leveled against Rustin to discredit the movement. It notes his 1953 arrest in California on "morals charges" and his past political affiliations, which critics used to argue he might "affect the cause". Rustin’s response was one of radical transparency; he acknowledged his past while grounding his current authority in his Quaker faith and a "dedication to an ideal" of nonviolence. The piece highlights his role as the "deputy" to A. Philip Randolph, illustrating how Rustin was the engine behind the scenes ensuring the march would not be "marred by any incidents".

Griffing, Junius. "Negro Plans D.C. March." The Sunday Oregonian, August 11, 1963.