Description

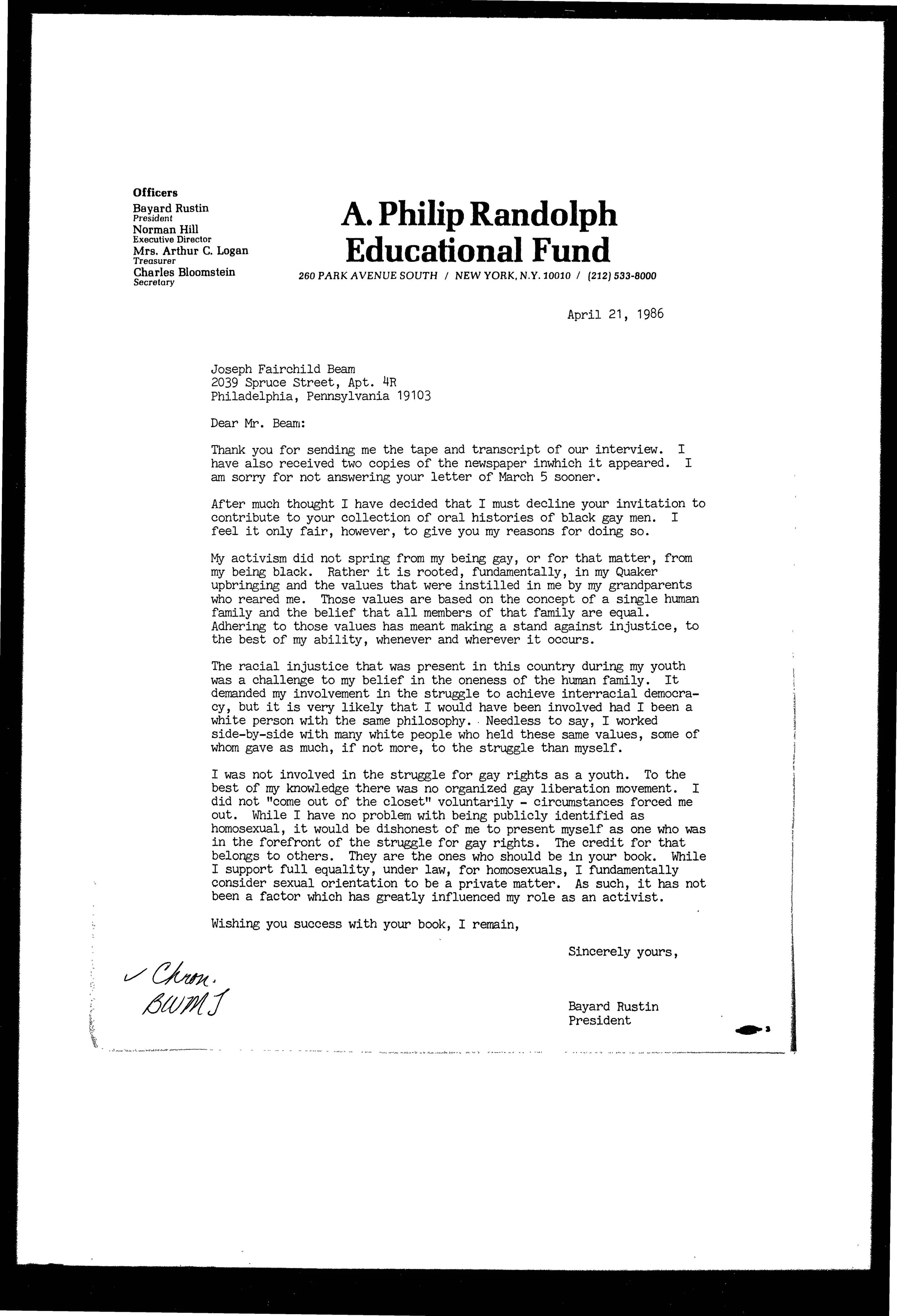

Writing to Joseph Fairchild Beam, Bayard Rustin declines an invitation to contribute to a collection of oral histories of Black gay men, offering instead a profound self-assessment of his own motivations. Rustin argues that his intense involvement in social struggle was not a product of his "identity as a Black man or as a homosexual," but was fundamentally rooted in his Quaker upbringing. He emphasizes that the Quaker values of his grandmother taught him that "every person had an 'inner light'" and that it was a religious duty to help others realize that light by removing social barriers.

Rustin further articulates a deeply private view of his personal life, stating his conviction that "one's sexual orientation is a private matter" and that he had never felt the need to make it a public issue. While he acknowledges that his openness as a gay man was often "forced upon" him by those who sought to use it as a weapon against the civil rights movement, he insists that his primary loyalty remained to the universal principles of nonviolence and human rights. This letter provides a rare, direct glimpse into how Rustin reconciled his various identities, prioritizing religious conviction and universalism over the identity politics that were becoming more prevalent in the late 1980s.

Historical Context

This letter was written to Joseph Beam, a prominent activist and editor, during a period of rising LGBTQ+ visibility and the burgeoning Black gay literary movement. At the time, younger activists were increasingly pushing for public leaders to claim their identities as a form of political resistance. Rustin’s response highlights the generational and philosophical divide between mid-century universalist activism and the emerging framework of identity politics.

By citing his 1953 Pasadena arrest and subsequent persecution, Rustin acknowledges that his sexuality was never truly "private" due to state-sanctioned homophobia, yet he remains steadfast in his refusal to let that persecution define his political mission. The letter serves as a crucial document for understanding how the "architect" of the movement viewed himself—not as a victim of his identity, but as a disciplined practitioner of a religious faith that demanded he fight for all marginalized people equally.

Rustin, Bayard. Letter to Joseph Fairchild Beam. April 21, 1986. Bayard Rustin Papers, General Correspondence.